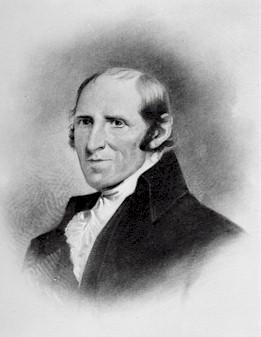

Timothy Pickering was born at Salem, Massachusetts, on July 17, 1745, of a family prominent since the early years of settlement. His father was sufficiently well-to-do to give him a good education, and he graduated from Harvard College in 1763. He later studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1768 but never attained distinction as a lawyer. Prior to the outbreak of the war he held a number of minor offices in Salem, among them selectman, town clerk, and representative in the General Court. He became a leading Whig in Salem and displayed talent as a pamphleteer in supporting the Revolutionary movement.

Commissioned a lieutenant in the Essex County militia in 1766. he studied military history and tactics and unsuccessfully sought to put the Massachusetts militia on an effective war footing. In 1775 he published An Easy Plan of Discipline for a Militia, which was widely used in the Continental Army until replaced by Baron Steuben’s manual. Pickering served during the early campaigns of the Revolution, rising to a colonelcy in the Essex County militia. On May 24, 1777, he accepted the post of adjutant general of the army. In the fall of that year he was elected to the newly organized Board of War of the Continental Congress, but also continued to serve as adjutant general until mid-January of 1778, since a successor was not immediately appointed.

While still a member of the Board of War he was appointed Quartermaster General in the summer of 1780, and authorized by Congress to continue on the Board, though his pay as a member and the exercise of his powers on the Board were suspended.

Pickering found the conduct of Quartermaster business handicapped by the lack of credit and the effects of a depreciated currency. Fully aware of these difficulties at the time of his appointment, he had proposed the use of ”specie certificates,” which stipulated payment in specie at a given date for all articles or services purchased on credit. If payment was delayed, such certificates were to bear an interest rate of 6 per cent a year until paid. Congress authorized their use, thereby enabling Pickering to obtain a few more supplies than would otherwise have been possible. Throughout the war, however, Pickering continued to be so plagued by the lack of funds that he wrote Congress: “If any other man can, without money, carry on the extensive business of this department, I wish most sincerely he would take my place. I confess myself incapable of doing it.” Harassed by lack of funds and scarcity of supplies, Pickering nevertheless, in consultation with Washington and acting in the double capacity of consulting member of the Board of War and Quartermaster General of the Army, effected the successful transportation of the allied forces from the Hudson in New York to the James River in Virginia for the siege of Yorktown and the capture of Cornwallis. This victory, in October 1781, proved to be decisive

As the war drew to a close, Congress turned its attention to the future military needs of the nation, and in response to a request for an opinion on the proper postwar military establishment for the United States, Pickering proposed the creation of a military academy at West Point where students might be trained as officers to command the defenses of the nation. For the most part, in these months, he was concerned with effecting various economies in the Quartermaster’s Department and attempting to settle his accounts as quickly as possible. He wrote Robert Morris that ”until I accepted this cursed office, though necessity compelled me to live frugally, yet I had the satisfaction of keeping nearly clear of private debts,” but that he was now much indebted. He wanted nothing more than a quick settlement of accounts and an opportunity to return to private life, where he might set about repairing the fortunes of his family. This settlement dragged on for many months after the war had ended, and Pickering did not relinquish his post until the Quartermaster’s Department was abolished, temporarily, on July 25, 1785.

Pickering lived to be eighty-four and remained active to the end. He had a distinguished public career after retirement as Quartermaster General. He held successively the offices of Postmaster General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State under Washington. He continued as Secretary of State under President Adams until he was abruptly dismissed on May 10, 1800, because of his opposition to administration policies. Thereafter he served in the Senate and later in the House of Representatives. As an outstanding member of the Federalist Party, he bitterly fought Republican administration measures and was especially virulent in his opposition to the War of 1812. After retirement from public life in 1817, he centered his interest on agricultural improvement and deservedly earned an important place in the history of New England agriculture before he died in 1829, rounding out a career as soldier, administrator and politician.